Pangalan Canal, the longest waterway in the world

The diverse history of this pharaonic structure

I want to take the suggestion of a good friend as an opportunity to write about the famous “Canal des Pangalanes”. While I almost always agree with my friend on matters concerning the red island, when he says that this “pharaonic structure” has been forgotten, I have to disagree.

The Longest Waterway in the World

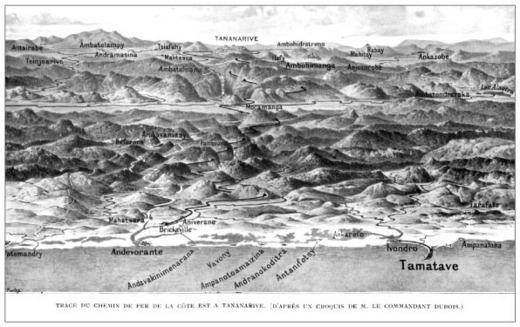

The Pangalanes Canal is the longest and perhaps the most unknown canal in the world. While its famous counterparts like the Suez Canal stretch over 165km and the Panama Canal over 80km, the Pangalanes measures a proud length of 645km. Its northern endpoint is Tamatáve or Toamasina, the major port city on the east coast. The southern point is located at…